[wzslider autoplay=”true” info=”true” lightbox=”true” exclude=”2404,2405,2380″]

Mount Shasta, an active volcano in the northern part of California. One of 22 peaks in the contiguous United States (a.k.a the Lower 48) to stand over 14,000 feet tall (or 2.6 miles or 4267 metres if you prefer). At 14,179ft it’s just a tad shy of the California giant Whitney’s 14,505ft (the highest mountain in the 48). Fourteen thousand is about as high as you can sensibly stand in North America and it makes the top 100 highest places in the world. So we decided to climb it.

Well, ‘decided’ is not quite how it happened. We were in our local blues bar with a few friends and one of them (you know who you are) was waxing lyrically about the joy of climbing Shasta. Clearly beer was involved. We immediately went home and booked a trip. The following day the same ‘friend’ modified the story to include the phrase ‘are you mad? I was 19. Don’t do it’.

Or at least that’s how we remember the events. His version may differ.

It was not fun. People describe this sort of thing as a ‘life highlight’, a ‘momentous occasion’, an ‘unparalleled accomplishment’. We describe it as the hardest thing we’ve ever done. With extra hardness. And we’re not doing it again.

Here’s the story. It’s not pretty.

[Update: when reading this please don’t confuse the word hard with bad. This was in no way bad, just very very hard.]

Day Zero

Mount Shasta City stands at 3,600 ft and is a pleasant place to spend a day doing last-minute shopping, avoiding alcohol, and generally killing time awaiting the main event.

There’s a couple of things you need to know to put everything you’re about to read in to context. The first is the kit. The second is something called Waste Alleviation & Gelling.

This is a 3 day walk up a snow-capped mountain. Given the lack of snow fall and the early arrival of Summer in California there was less snow than is normal but that didn’t change the load we were required to carry / wear.

[twocol_one]

- Ice Axe

- Hiking poles

- Hard plastic, uncomfortable snow boots

- Crampons

- Socks (2 pair)

- Underwear (2 pair)

- Base layer trousers (long johns)

- Base layer top

- Soft shell long trousers

- Hard shell long trousers

- Gaiters

- Medium weight fleece

- Hard shell outer jacket

- Large puffer jacket

- Face snood

- Fleece hat

- Peaked cap

- Hard hat

- Climbing harness

- Glove liners

- Ski gloves

- Camp booties

- Air mattress

[/twocol_one][twocol_one_last]

- Inflatable pillow

- Sleeping bag

- Sleeping bag thermal liner

- 3 man tent

- Head light

- Pen knife

- First aid kit

- 2 liters of water

- Sun block

- Cameras (lots of)

- Toilet paper

- Wet wipes

- WAG bags (2)

- Ziplock bags (random collection of)

- Alpine glasses

- Camp stove (parts of)

- Camp stove fuel (3 bottles)

- Cooking utensils (various)

- Plate, cup, spork

- Breakfast (3 days)

- Dinner (2 days)

- 30 snacks (cliff bars etc)

- 85 liter backpack[/twocol_one_last]

In Andy’s case all that added up to about 55lbs, Deanna’s was a tad less but not by much. Communal items such as the cooking stove, fuel, pots, breakfast and dinner were divided between the 5 hikers and the 2 guides. Additionally the guides carried all sorts of extra stuff like (heavy) spare water and rope. These guys are amazing.

And that brings us on to the Waste Alleviation & Gelling system known as WAG Bags. Shasta is designated Wilderness, which means it has the highest protection the Federal government can offer. You are allowed to leave nothing behind, take nothing out, and leave no trace (there’s no paths in other words). And that, unfortunately, means you have to carry all your excrement home with you. The WAG system is a sheet of paper with a target on it. The idea is that you squat over paper, try to hit the target and not get frost bite on your derriere. You then CAREFULLY fold the sheet and place it inside a brown paper bag. The bag contains a small amount of cat litter. Taking the second brown paper bag, you pour its cat litter in to the first bag and then place the whole thing in to the second bag. You then scrunch everything up as tightly as you can and place it in the zip lock. If you’re us, you then place that in another zip lock. And it still smells. The whole mountain smells of cat litter and poo.

Day One

The day starts at a respectable 9am with a meeting of our guides Joe and Ryan, and our fellow hikers. We’ll keep their names off this blog out of respect for their privacy but you’ll see them in the photos. There’s 3 of them. And we liked them (a huge improvement over our previous Grand Canyon experience). By 12 we’d driven to the trail head at Bunny Flats. This large area is often covered in deep snow until late June; today it’s bone dry and crisp. It stands at a mere 6,950ft.

From here we suit up, and start the (exceedingly) slow walk up 1,000ft of mountain, covering about 3 ½ miles to Horse Camp. The hike is mostly just a nice walk through the trees with little to remark upon. Horse Camp is the last place on this trip that has a toilet, water and even an emergency shelter built-in the 1920s. There are patches of snow on the ground and the guides report that just 2 weeks earlier the pack was 5ft deep. Things change fast around here.

We pitch tents, and spend the evening getting to know our fellow travelers. The camp host is leaving after 7 years of keeping tourists safe and so we’re honored to be allowed a rare camp fire. It turns out that San Jose is strongly represented around the communal fire, with one chap actually living just around the corner from us. It’s a very small world.

Dinner tonight is fresh veggie soup followed by chicken burritos and chocolate cookies. Perfect.

Strangely, even though we’re barely at altitude, all 5 of us have killer headaches and so we retire early and get some sleep.

Day Two

We arise with the sun, or there about, and are greeted by our guides making nasty nasty coffee and yummy yummy oatmeal and granola. One of our team cuts his oatmeal with Jerky. Apparently, that’s not a good idea.

And so our first real hike begins. The walk out of the campsite is on a stone causeway (the campsite is not in the Wilderness) and it’s horrible. Basically, while juggling a huge backpack and the early effects of altitude, you have to walk on stepping-stones for about a mile. Whoever invented this is a sadist.

Eventually, the dry floor is replaced with lovely hard snow and we start the slow process of walking up the mountain. Our goal is the Lake Helen campground at 10,400ft. Shortly in to the climb we’re overtaken by a group on skiers. Apparently, you can place skins on the bottom of skis and they enable you to slide up hill. We’ve never seen such things so we pause and watch them slide by.

The pace is terrible. We’re walking where we want, kicking each foot in to the deep powder and raising each heavy leg. It takes hours to make little progress and distances confuse all.

When we finally spy the campsite it’s just a little further than our current rest stop but that ‘little’ takes another 90 minutes. It’s not so much that the air is thin and we can’t walk, it’s just that without the day-to-day markers you use to judge life, distances are massively compressed.

The lake (it’s not now, and never has been a lake) is just a tiny area of flat land on a steep mountain side and is packed with tents, so we elect to camp a little lower on a bare outcrop. Some of the group got to pitch in the snow, we were lucky enough to have dirt.

The early evening was spent playing in the snow and practicing our emergency arrest maneuvers (things to do if you’re falling off a mountain). Sadly, at 10,000ft one of our team had a brief coming together with his ice axe and painted the snow a delicate red. Following another superb dinner (sun-dried tomato soup with sausage and bean couscous) it was decided that the bleeding one had to go to hospital. Pulling his red underwear atop of his tights, Ryan escorted our defeated team-mate off the mountain while we turned in for an early night. Tomorrow is the big day and it starts early.

Day Three

Hour Zero (1:30am)

It’s dark. It’s cold. Very cold. We awake to the sound of Ryan and Joe making more of that nasty coffee. Apparently, for Ryan, just popping back to the trail head in the middle of the night is no big deal and he’s now ready to climb the mountain. Super freak.

Hour One (2:30)

Leaving our tents blowing in the breeze, we head up the mountain guided by a stunning Milky Way and about 60 head torches. This is a mass assault on the summit. We’re walking in single file, two tourists per guide using something we think of as the Shasta Shuffle: leaning on the ice axe, lift the leg furthest from the side of the mountain forward and drive it in to the snow; now move the other leg forward. With both firmly planted, move the ice axe forward and rest. Congratulations, you’ve just moved 18 inches it took 2 seconds.

Towards the end of this hour we stop to rope up. The mountain has become so steep that you can rest your head on it while still standing perfectly upright. For safety, the guides have decided that we should be tied together. The walk continues.

Hour Two (3:30)

At 10,800ft Deanna’s nose starts to bleed. She chooses to ignore it and walks on. Sometimes you just have to be in awe of this lady. Finally we get to rest and pee. Joe cuts seats out of the side of the ice field for us, so that we can relax without falling off. Andy spends his time firing up the GoPro rig he’s been carrying since all this started. We didn’t film days 1 or 2 because they were nothing special. The early part of day 3 was too dark and so this is the first chance we’re going to get to see if months of preparation and experimentation will pay off. Even though it’s not been used, one of the batteries is already dead due to the cold and needs changing. Not a good sign.

The walk continues.

Hour Three (4:30)

They say it’s always coldest before the dawn and that’s certainly true at 11,300ft. The wind and the cold bite and still we walk. We’re climbing up Avalanche Gulch on the North side of the mountain. Everyone else seems to be swinging NNW in an attempt to breach The Red Banks but we swing NNE to find the path less trodden. Our guides don’t like walking with others. Others cause rocks to fall. Others cause avalanches. Others are bad.

Hour Four (5:30)

The sun comes up at 5:30 and we’re near the top. It’s just over there. We can almost touch it. We can see the sunlight painting the snow a delightful, bright, warm yellow. We walk towards the light.

Hour Five (6:30)

It’s almost 7:15 am when we finally cross the line from shade to light and we get to rest atop the hardest climb we’ve ever undertaken. The warmth of the sun breathes new life in to us as we learn we’d misunderstood. That was not the hardest climb. The next bit is known as Misery Hill but we call it Asshole Hill because it has THREE (count em!) false tops. And it’s steep. Like the wall in your living room is steep.

Hour Six (7:30)

After a long break we walk towards the terror of Misery. It’s just a long pile of shale. There’s hardly any snow on it and it doesn’t look that bad. We’re now at 12,000ft. We pause for food and to shed layers.

At each false top there’s nothing to do but pant, moan, and walk on.

Hour Seven (8:30)

Finally, Misery is defeated. We’ve climbed the false tops and the real thing is magnificent: a flat field of snow stretching maybe ¾ of a mile in front of us. We’re walking across the apex of where two glaciers meet at 13,500ft. The mountain falls steeply away in every direction. We swear you can see the curvature of the Earth from up here (*you can’t). In the distance Shastina, and Mount Lassen look tiny. Everything looks tiny.

Hour Eight (9:30)

We’re on our last reserves and the walk atop the glacier takes forever. There’s a final tiny little hill to climb to reach the summit. It’s only 600ft but we just can’t do it. Against the urging of our guides, we all slump to the ground and take off our packs. We’re not moving. It seems the group decision (voiced by Andy) is that we’re not going to the top. It’s too far. We’re too tired. We sit in silence, exhausted. It’s over. We’re going home. Time passes.

Hour Nine (10:30)

Deanna rises slowly and picks up her pack. The whole group looks at her with complete confusion. She’s going to the top. Like a dog kicked once too often, we too rise and pick up our packs. Here’s something you need to know about Deanna, she has more determination and deeper wells of will power than anyone else you’ll ever meet. It’s either humbling or in this case, really freaking annoying.

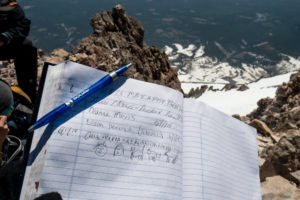

We make it to the top at 11:15 and Andy immediately falls over and cuts both his knees open. We sit in silence. Neither happy nor sad. Just sick. Tired. And very aware that we have a long walk home. There’s a cool book on top that you get to sign. When the book gets full they take it down to the town’s Visitor Center for all to see. They replace the book every 3 months. 30,000 people a year sign it. Andy wrote something rude in it. Deanna just signed her name.

Hour Ten (11:30)

We walk off the peak at 11:30, exactly 15 minutes after we arrived. Reaching the far side of the glacier requires dodging a lot of WAG bags in use. Apparently at 14,000ft the human body likes to express itself. The 60 people up here are like dogs in a park.

Hour Eleven (12:30)

At the top of Misery Hill we bump into the beardy-weirdy park warden and he’s a delight. While we’re all just trying not to fall over he waxes lyrical about the people who live in the tunnels under the mountain.

The story goes that back in the day, there was a floating continent in the Pacific called Lemuria, populated by tall thin people rumored to be from a distant star. The continent drifted in to California and, as always happens when a floating continent meets a fixed one, it sank. However, CA is built on an underground lake and so the Lemurians drifted down and East and eventually stopped under Mt Shasta. The people, who were talented miners dug their way out and now live in a tunnel complex under the hill. They are often seen coming and going through crystal controlled portals in order to trade gold with townsfolk. It was noted by the cynical that all the portals are conveniently near the highway, and also, that Shasta City handily has a lot of shops selling crystals.

Anyway, it’s a true story. Honest.

Hour Twelve (1:30)

We’ve crossed The Red Banks and are now standing atop a very long, very steep snow field. It took us almost 6 hours to climb up this beast, and we’re going to be down it in 30 mins. We’re going to glissade. Glissading is the art of sitting on your bottom and falling off a mountain. You use your ice axe as a brake but frankly that’s just so your hands freeze and you feel in control. This really is falling off a mountain. We thought it was going to be a fun highlight. It’s not. It’s cold, terrifying and out of control. Think of it as luge or bobsledding, only without all that safety equipment.

Hour Thirteen (2:30)

Being in camp is a mixed experience. We’re happy to be off the dangerous part of the mountain and the oxygen rich 10,000ft air tastes great. However, we’re not here to enjoy ourselves or to relax. We’re taking down tents and loading our backpacks to back-breaking weight again. An hour after we arrived and we’re off to learn new snow walking techniques.

Hour Fourteen (3:30)

We’ve learned a lot in the last couple of days about how to walk in snow but there’s always room for more. This hour’s lesson is in the Plunge Step. Basically, this is a very fast way to walk down hill in powder snow. You slam your heel in to the ground like you hate it and bounce forward to repeat. It’s as fast as glissading but when you encounter hard snow your knees explode. It’s not actually that much fun. The second technique is Shoe Glissading or Standing Glissading depending on whom you ask. It’s skiing without actually bothering with those pesky skis. It’s easy but you fall over a lot and then it becomes a tad tricky to get you and your pack out of the soft snow. At some point we meet a woefully under dressed chap with little equipment and even less of an idea, heading up the mountain. He asks where the campsite is and we break his heart. The guides spend 5 mins teaching him how to walk properly and use an axe. Nice people.

After an hour of bouncing, slipping, sliding and falling off the mountain we run out of snow and move to dirt.

Hour Fifteen (4:30)

We walk. Nothing to report. Just rubble covered tracks that terminate in the causeway we hated when we were young, fresh and energetic just 2 days ago. Arriving in camp is quite the joyous experience. There’s a toilet and all the fresh spring water a person can drink. We soak in the sun and embalm ourselves with H2O.

Hour Sixteen (5:30)

We depart Bunny Flats sated with fresh water and Jerky. The walk is pleasant in the later afternoon light as we make our way through the forest. Everything we just said is true except the ‘pleasant’ part. We’re exhausted: this is just a long walk back to the car.

Hour Seventeen (6:30pm)

We arrive back in the parking lot at 6,950ft at 7:15. It’s been a very very long day and we can hardly talk. The guides try valiantly for group high fives but instead we all shuffle off to deposit our WAG bags. An hour later we meet again in town to return rental gear and exchange phone numbers. The group we hiked with really are good, solid people we’d be happy to spend normal time with. The guides however, are super humans and we’re not worthy. They were better than amazing and we’ll be eternally grateful for their guidance and support.

Afterword

In time we’re convinced this is going to be a highlight but right now we’re fully prepared to burn our backpacks and never set foot on a mountain again. On returning to civilization, we fire up our phones and discover the world is very concerned about us for reasons we’re not clear on. We later discover that 6 people spending a very similar time on the next mountain over have died in a freak accident. At no point did we feel in real danger but it is sobering news.

UPDATE

It’s now been a week since we summited. The exhaustion has been replaced with a sense of accomplishment and pride, and we’re beginning to see our backpacks as friends that take us to interesting places rather than enemies that are out to hurt us. We might never go to the top of Shasta again but we’re already making plans to go one better. This is still the hardest thing we’ve ever done, but then isn’t pushing yourself to be better the point of life?

Come on, talk to us!